The History of Urban Form Lecture 01: What is a City?

This is an excerpt from Otium Issue 01. To read the full issue, click here. This lecture is also available in video form here.

A note from the editor:

A note from the editor:

What follows is an edited transcription of Doug Allen’s first lecture of his legendary course, The History of Urban Form, recorded on August 21st, 2013, at Georgia Tech – the last semester Doug was able to teach. Doug taught this course for over 30 years and inspired hundreds of his students—myself included—to pursue careers in urban design and planning. In fact, the course was voted the most popular elective offered on the entire Georgia Tech campus. We are excited to make this material publicly available to ensure that his lessons continue to be taught.

Converting a lecture into an essay has its unique challenges. Doug was a master orator, but how does one translate his voice onto a page? What follows is our humble attempt to present the information contained within his lectures, remaining as true to the original text as possible, with some steps added for clarity. Additionally, we took the opportunity to produce new diagrams and photographs, improving upon Doug’s self-criticized skill at PowerPoint graphics.

Over time, we hope to provide this same treatment to the remaining 39 lectures in the series, culminating eventually into The History of Urban Form book. We hope you will join us in this endeavor.

Paul L. Knight

October 8, 2016

Part I: Kostof, Mumford, and Allen

What is a city? This seems like a simple question, but it is surprisingly difficult to answer. We all have an innate sense of what a city is. We all know when we are in one. But there is a risk of falling down a rabbit hole once we begin to write down the characteristics that we think are required to define a city. So we must first recognize that no definition, including my own, is totally satisfactory.

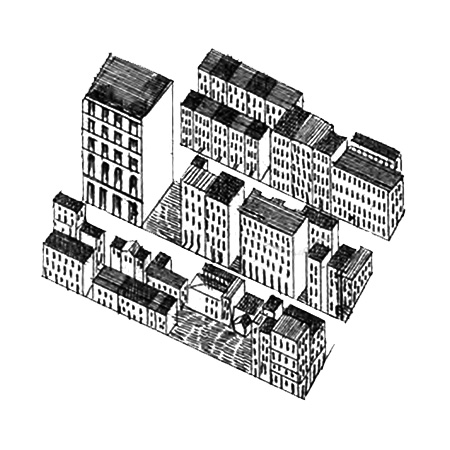

Let’s first see what others have said about this. Spiro Kostof, a great architectural and urban historian, offers nine points he uses to define a city, taken from his seminal text The City Shaped:

1. “Cities are places were a certain energized crowding of people takes place.”

There is always some discussion of density and crowding and so forth, but I find this to be a terribly unsatisfactory qualifier. When I go to a Braves game, there seems to be a lot of energy and there is a lot of crowding. But Turner Field is not a city.

2. “Cities come in clusters.”

There is always a kind of hierarchy in how developments distribute themselves in an area. Around Atlanta, for example, there is a kind of ring of smaller cities like Macon and Augusta and Columbus. And then between Macon and Columbus there are still smaller cities. Each of those cities, whether it’s Macon or Columbus or Atlanta, is an economic center for a lot of activity of people that are somehow associated with that place. This hierarchy we see today interestingly enough goes all the way back into the ancient world. In some cases, as in the case of Ancient Rome, this hierarchy is actually set into a kind of law that has to do with the physical agricultural territory that was attached to a particular city (we will come to this later in the course).

3. “Cities are places that have some physical circumscription.”

This is easy to see in cities dating from the Middle Ages in Europe because there is a wall around the city. It was pretty clear. You were either inside the wall or you were outside the wall. You were either ‘intramural’ or ‘extramural’ from the Latin “mura” meaning “wall”. Intramural athletics means that different clubs and groups at Georgia Tech play one another. Extramural means we play Clemson or Lake Forest; we play someone outside our wall. But in the complexity of the contemporary city, like Atlanta, it is very difficult to say where a city begins and ends. When you come down Interstate 85 in a car there is a little sign on the side of the road, lost amongst many other signs, that says “City of Atlanta.” Other than that there is no clue whether you are actually in Atlanta or not. So it’s a little more ambiguous today than it was historically.

4. “Cities are places where there is a specialized differentiation of work.”

5. “Cities are places favored by a source of income.”

Cities are economic engines with income, trade, intensive agriculture, the possibility of surplus food, physical resources, and so forth. You don’t think about it when you go to the grocery store that this is one of the major benefits of cities. You don’t have to chase the chicken around the yard like my grandmother had to do.

6. “Cities are places that must rely on written records.”

This is critical. Writing is a fairly recent human invention in its current forms, going back to about 4000 BC. It originally had to do with the need to record lists of things from trade, food, population counts, preparations against attack, etc.

7. “Cities are places that are intimately engaged with their country side.”

There is agricultural territory normally associated with a city. In the days before airplanes and trains and boats most produce had to be grown locally. It was like milk today. We don’t import milk from Peru. It would go bad too soon. So agricultural products that are associated with the territory close to the city suggest that prior to the modern world there was always an agricultural territory that was attached to the city linking them economically.

8. “Cities are places that are distinguished by some kind of monumental definition.”

Now by monument—and we will come to this more in a moment—what Kostof is really talking about is memorial, or memories. This is something that makes us unique among the animals so far as I can tell. It’s true that salmon go back to the place that they were born to spawn. It’s true that my dog knew how to get home when he was lost. But as far as I know my dog did not know the name of his grandparents and he did not desire to have a head stone when he passed away. This human trait to enshrine for future generations the memory of something that we think is important in the present makes us unique. And we see all cities going all the way back to the earliest forms of human settlement have been associated with this monumental function. The monument alone does not make a city, but cities do always embody a monumental function.

9. “Cities are places made up of buildings and people.”

I have always been struck by the differences between an architect’s view of the city and a city planner’s view. When architects talk about cities, they talk about the physical thing: the buildings and bridges and infrastructure. When planners talk about cities, they talk about people. And so there is a rhetorical question here: which is more important, the people or the city? We will explore this question throughout this course.

Kostof elaborates on these points much more than I will here so I invite you to reference his book. I do find his points useful and I find them important. But having said that, taken all together they are just too complicated. It reminds me—and before I go any further trust me that I’ve never done this as I’ve been happily married for 40 years—but I can imagine people going on dating websites looking for a mate that is educated, with a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from Northwestern University, that’s also a great cook, and so on and so on. You end up with this list of 14 things and guess what, you’re not going to find anybody. And I think there is some aspect to that here. Kostof’s points are a little too much to actually be very useful.

Lewis Mumford, an historian and writer, said this: “The city is a related collection of primary groups and purposive associations: the first, like family and neighborhood, are common to all communities, while the second are especially characteristic of city life. These varied groups support themselves through economic organizations that are likewise of a more or less corporate, or at least publicly regulated, character; and they are all housed in permanent structures, within a relatively limited area. The essential physical means of a city’s existence are the fixed site, the durable shelter, and the permanent facilities for assembly, interchange, and storage; the essential social means are the social division of labor, which serves not merely the economic life but the cultural processes.” [“What is a City”, Architectural Record, 1937]

Again, like Kostof this is quite complex in all of its qualifying statements.

I like the definition provided by Lewis Wirth, a sociologist, a little bit better. In his essay “Urbanism as a Way of Life”, he identified four characteristics that all cities have:

1. They are permanent constructions, or at least have the pretense toward permanence. When a city is built the idea is that its going to be there for a very long time.

2. They have large populations.

3. They have higher densities than rural areas.

4. There is a lot of social stratification and social heterogeneity.

Those are fine points, but again, it doesn’t help us very much for applying these toward a variety of cities across time and space to really understand how we might differentiate these things formally one from the other. But I like the final concluding statement that he makes: “A serviceable definition of urbanism should not only denote the essential characteristics which all cities—at least those in our culture—have in common, but should lend itself to the discovery of their variations.” That strikes a chord with me—what we have in common. I think its very easy to talk about differences and what separates us. We have different religions. We have different skin colors. We have male and female, different ages, and all kinds of demographic things that are all about differences. But in the end those demographics are really about finding what people have in common. And it is looking for what is in common that leads me to my definition.

After almost four decades of teaching this course, I thought I should obligate myself to come up with my own definition. So here it is:

“The city is the largest man-made artifact in human history. It is a political association manifest as a collective work of architecture built over time. A city contains two orders: a Political Order and an Economic Order.

“The Political Order is a framework of common elements owned collectively. The Economic Order consists of individually owned parcels and their occupants within that collective framework.”

Part II: Constitution and Representation

Now having said that, let’s start to tease this out a bit more. I said that all cities have two orders present, one political and the other economic. The political order I call the Constitutional Order because it constitutes the city. It contains four elements: boundaries, streets, public places, and monuments. That’s it—four. As hard as I have tried I cannot come up with a fifth one. In and of themselves these things are meaningless. It is only once they are occupied later by the economic order that they become animated. For the sake of this course I will refer to the economic as the Representational Order.

Constitutional Order

The constitutional order brings a collective structure into being. It is political in nature. It organizes society. It separates us from one another and joins us in a collective structure. It is prior to individual building. Every city has a constitutional order.

Boundaries

When I say the word “boundary” what comes to mind? Most people might think of extramural boundaries, like the walls of a medieval city. You’re either inside the wall or outside the wall. But there is another kind of boundary, one that is intramural, like the property line between me and my neighbor. (And by the way you may have come across these words before, “extramural” and “intramural”, in sports. The Latin “murus” means “wall”. So in intramural sports, Georgia Tech students play amongst themselves, within the campus wall; extramural, they might play Clemson, outside the campus wall.) Or the wall between my living room and my dining room. But in this example, which room does the wall belong to? The wall constitutes each room’s existence. Without the wall I wouldn’t have a living room and a dining room. The boundary is shared by the two rooms. And it is shared by a larger concept called a “house.”

Coming back to the parcel line adjacent to my neighbor, who owns that property line? Who actually owns the property line? You do; the city. If we are going to have setbacks and zoning requirements and other kinds of things from where do those regulations proceed? The property lines. A seven foot side yard setback, e.g., is measured off of the property line.

Let’s look at this etymologically. What is embedded in the word boundary? Bind. Binding. To bind. Books, for example, having a binding. The pages are bound together. Or take my wedding band, the symbol that I am married. These are the ties that bind. So the word boundary actually has a double meaning. It simultaneously separates and joins. It separates and constitutes the living room and the dining room but it joins them together in a larger structure that we call the house.

Circling back around, the boundary is the fundamental tectonic unit of the city. It separates and joins discreet identities into a collective whole. It is constitutional, owned by the city. It is owned by the political entity, the political association, or the collective association. This is critical in understanding how cities actually operate, particularly from the stand point of designing a city.

Streets

The Street is the primary structural unit of the city. They allow us to communicate and to move about. They constitute the order within the collective whole. Streets are complex institutions with great social, political, and economic depth. Giving them over to the single function of traffic movement as we have done over the last 100 years depletes them of their historical depth and their historical role. What I mean by that is that since the advent of the automobile we have actually come to a point where we tend to think of streets as something you just drive on. But the street is actually the public right-of-way. It has many names, like via, meaning “way,” and strada, meaning “pavement”. And they have many names, like 16th Street, e.g., which conceptually is a very different thing from Old Flintlock Trace or something in a suburb somewhere. They have different associations that come to mind. But the public right-of-way is the street. And streets are complicated. Revolutions begin in streets.

Streets are the primary structural unit of a city just like a column grid is to a building. Forty years from now we might decide to change this lecture hall to a cafeteria, but the one thing we are not going to move is the columns. Because if we move those columns the building collapses. Streets are like that. Once they are built they tend to stay with us for a really, really long time. In Damascus, e.g., there is a street called Straight which is about 4,000 years old. When you are in the old city of Jerusalem today walking through the Souq Khan El Zeit you are walking down the Roman cardo that was constructed in about 130 AD. Streets, once they are built, stay with us for a really long time and they shape and form the nature of the city itself. They give form to it. That is largely what I mean when I say “urban form.”

Public Places

I am going to be deliberately vague here, maybe even a little too weak, but public places are places where the public gathers. These are locations outside of the domestic environment where one is aware of their identity as a citizen. That’s the important part. That’s the qualifier. The public may gather in a shopping mall, which has all of the appearance of a street, but is it a street? Is it owned collectively? No. It has doors at either end and you can shut it down at 10 o’clock at night. It’s a fake street, an ersatz street that is built inside of a warehouse. In fact, at Lenox Square Mall here in Atlanta there is a little obelisk in the middle, and I think there’s a fountain, and it signifies the idea of a town square. And I have always wondered what town is it the square of. It’s not the center of the city. It is not owned by the city, but it is developed in imitation of a real street.

Again, with the advent of the automobile and the complexities of the modern world in the 20th century, public places often times have become quite ambiguous. It is difficult to sort out, but for now let’s just say that typically the public place is the place that is associated with the functions that remind us that we are citizens. The July 4th Peachtree Road Race, e.g., ends in Piedmont Park as opposed to simply a club house in a condominium building.

Monuments

Public places typically serve a variety of roles, one of which is a memorial function. They become the repositories of memory expressed through monuments. There is a kind of confusion that needs to be addressed here. When one says “monument” most people will think it’s a really big thing because we tend to associate exaggerated size with being monumental. That may mean that it has taken on the characteristics of a monument, but if it does not stand for something else then it does not play the role of a monument. The Coca Cola building here in Atlanta may be really big. It has Coca Cola written on top of it. But is it a monument? No. Because it doesn’t represent anything other than itself.

Monuments can become quite complex. They might include public buildings. The Lincoln Memorial, e.g., was built in the 1930’s after Lincoln’s reputation had been rehabilitated in a number of ways. I won’t get into it here, but he was actually ridiculed while he was president even from people in the North. In fact, a reporter in a Chicago newspaper referred to him as a monkey after he gave the Gettysburg Address. Anyway, we built the Lincoln Memorial. But Lincoln isn’t buried in there. Instead, what does it represent, symbolically? It stands for the concept of justice, of unification. The number of columns stand for the number of states in the old Confederacy and the Union. The unification of the nation. And what does the memorial face? The public building which is the embodiment of the legislative branch of the government with its dome at either end of a long street we call the Mall. And Martin Luther King, Jr., appropriated this space and symbolism in 1963 to give his very famous speech.

So, these kinds of public spaces together with their symbolic functions have the potential to transform us in light of the concepts being shared. Monuments stand as a physical form of remembrance to guide our future generations. The court house square, the Capitol, these all are forms of that. In the ancient world they might contain a temple; they might contain another kind of public building; they might contain the house of the king; they might contain something which is intended to ensure the welfare of the community as a whole. That’s the intent. And the purpose of the monument is to obligate future generations to remember something that the builder of the monument believes to be important. So how long is a monument supposed to last? Forever.

Economic Order

On the other side of the coin, we have the Economic (or Representational) Order. This order animates the constitutional frame and gives it meaning. The Representational Order is economic in nature. It changes more rapidly over time than the constitutional order. Let’s go back for a minute to my ersatz street in the warehouse we call Lenox Square Mall. I am of a certain age that has allowed me to bear witness to a number of changes here, where the cookie store changes place with tie store which changes place with the furniture store. Things come and go out of business along the “street.” But what doesn’t change at Lenox Square? The column grid, the leasing depth, etc. You can buy shops side to side but you cannot encroach on the collective space in the center. And that is an analogy for how the city operates.

The Economic Order fleshes out the political, or constitutional, framework. It consists of houses of all types including farms and industrial productions. These are all part of what I would call in the larger sense the domestic realm including markets, commercial, office, and institutional buildings that are not associated necessarily with the constitutional frame. The vast majority of architectural production falls within this category. Individual acts of building over time animate and give meaning to a large or small degree to the political framework.

Now, comparing the two orders, the Constitutional Order is more or less permanent and the Representational Order is more or less changeable over time. Over here at West Peachtree Street and 5th Street, I remember, in my lifetime, when John Smith Chevrolet, a dealership, was on one of these blocks, and there were a series of houses on another. And there was one on this corner about where I am standing that I got my first stereo repaired. It then became a parking lot, and then there was a night club called Cafe Erawan which eventually changed because Georgia Tech bought it. And now the whole area has been redeveloped and we are sitting in Tech Square. But what didn’t change? The public right-of-way. These various uses simply plugged in to this political frame over time. And as they come and as they go, they animate the boundaries in significant ways and they give the city meaning. The occupants, the people, the uses, give the Constitutional Order meaning. But the framework is prior to individual habitation.

In the United States today, the first three elements of the Constitutional Order are controlled by Subdivision Regulations. The monument, by its nature, is representational as it stands for something else. But once it is constructed, it then flips categories and becomes a permanent part of this constitutional, political order. The Economic Order is controlled by zoning ordinances, at least since 1926—we will discuss this extensively later on in the course.

Now, let me pause for a moment before I move on and ask you a rhetorical question. Here we are in this Georgia Tech lecture hall at the intersection of 5th Street and West Peachtree Street. Where does that come from—5th Street and West Peachtree Street?

There are—and have been—a lot of great cities in this world. Stockholm, Moscow, Santiago, Lyon. But we are not going to talk about those cities because I have to edit the content of this course in some way. As important as Moscow might be on the global scene today, by traveling through Moscow’s urban history we don’t get here at 5th Street and West Peachtree Street. The point of view of this course is from this intersection looking backwards to ask ourselves the question: How did we arrive here? How did we come to a point where we have an intersection called West Peachtree and 5th?

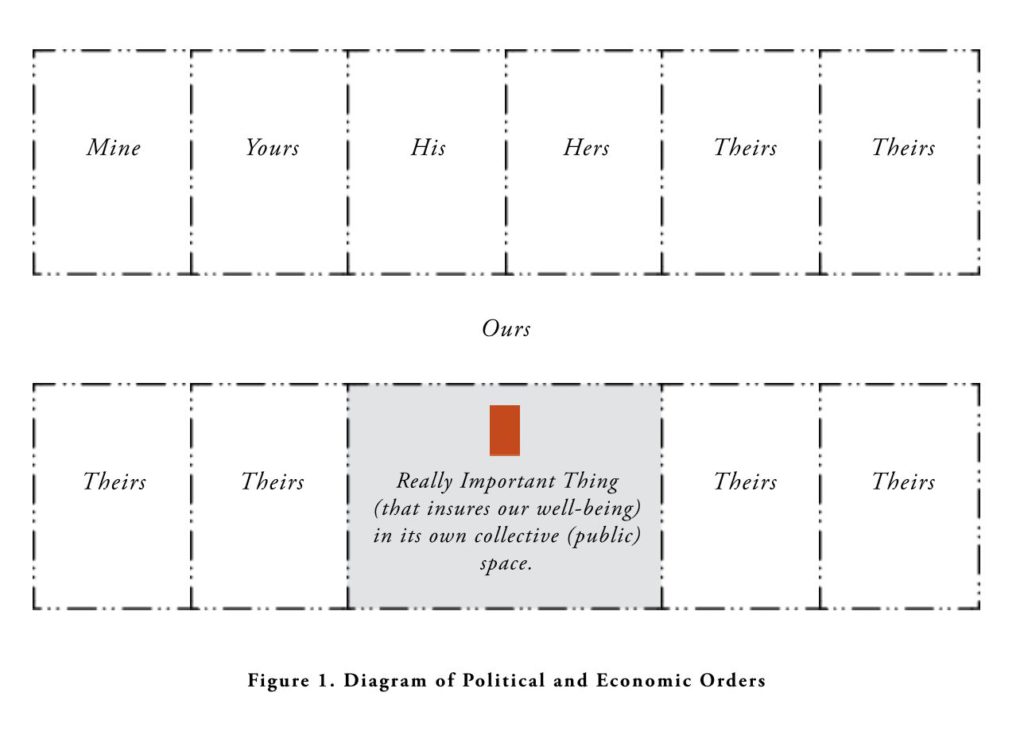

Part III: Mapping the Constitutional and Representational Orders

Now, let’s see how this constitutional frame is distributed in space. Before there is a mine and a yours and a his and a hers and theirs, there has to be something that differentiates undifferentiated territories, subdivides it into parcels, and forms the collective structure. Figure 1 maps this out (it doesn’t have to be a rectangle, but for the sake of this diagram it’s easier to show that way). I can’t support this for sure, but I believe that this is the beginning of human consciousness in the modern sense. Once we are able to say that this is mine and this is yours, what the parcel line does is inscribes a kind of ethical behavior of how I treat my neighbor in his or her absence. J.B. Jackson, my professor at Harvard, said that boundaries are what made farmers out of wanderers, neighbors out of farmers, and citizens out of neighbors. I think that’s true.

Now, since Adam was in paradise, he didn’t need a street. But once he was expelled from paradise and had a neighbor, he needed a street because all of a sudden he was in a shared world. The street is the collective space. It is ours.

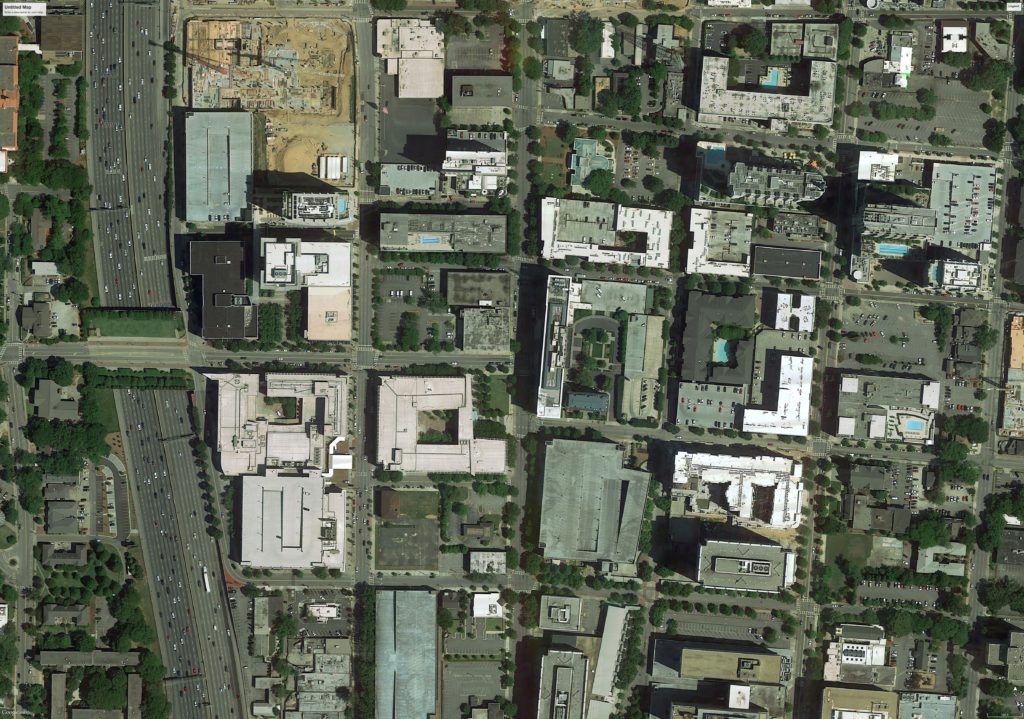

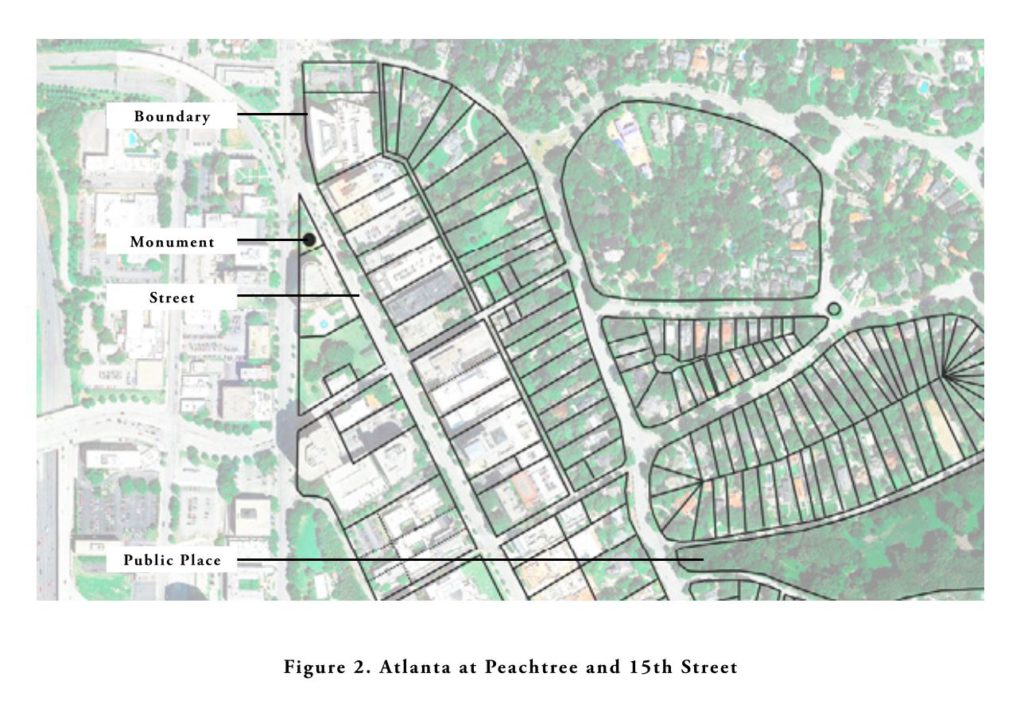

Figure 2 shows a portion of Atlanta at Peachtree Street and 15th Street with the collective frame articulated. In this case we have irregular shapes, but the constitutional and representational orders are there.

Again, it doesn’t have to be rectangular, but, having said that, rectangles are particularly useful. Unless you sleep on a round bed, or sit on a round sofa, or drive a round car, rectangles tend to be fairly useful forms for us.

In Atlanta’s early development (which we will come back to at the very end of this course), the important thing was (and in many ways still is) the railroads. By the way, Spring Street got its name because it led to the spring near the depot. There was a land lottery that divided up the territory. Each individual owner in the lottery could subdivide their section in any way they saw fit. Atlanta never had any kind of artistic intent. The person who laid it out, Stephen Long, was offered a land lot as payment and he said no thanks—“[it] will be a good location for one tavern, a blacksmith shop, a grocery store and nothing else.” History can be so entertaining. Now its a city of 6 million people.

So, look at how all of that laid down in the crudest possible way influenced the shape of the city over time. Figure 3 shows the original 1853 map of Atlanta overlaid onto a recent Google Earth aerial photograph. The pattern persists. It really is astonishing. We get so caught up in our present lives that many of us fail to see the incremental changes taking place around us, changes that can add up and substantially alter our surroundings. And yet given all the changes we’ve had in Atlanta—civil rights, skyscrapers, etc.—its urban form has been a rigid canvas.

Now, compare that example of downtown Atlanta’s form to that of an area up GA 400 in Alpharetta, Figure 4. Form ultimately has to do with our intent. What I would like you to realize here is that when downtown was built there were no regulations whatsoever—none. You just subdivided your land the way you saw fit. This area in Alpharetta, on the other hand, is probably the most heavily planned environment that I can think of. Everything you see here—the buildings, the curb cuts, the creeks, the roads—has been subject to some form of regulation.

Part IV: Conclusion

In closing, the Constitutional and Representational Orders are not just found in American cities. They are universal elements found all over the world. Regardless of our different cultures and languages and histories, we share these common denominators of our respective urban forms. So I will end this here for now and leave you with a series of Google Earth images. As you study them, I would like you to take note of the boundaries, streets, public places, and monuments, and see how all the houses and markets and shops are distributed within that framework.