Visiting the Greatest Grid

The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011 is an exhibit on display at the Museum of the City of New York through April 15, 2012. It explores the comprehensive history of Manhattan’s master street plan. Following is a review of this exhibition as well as a critique of a concurrent exhibition titled The Unfinished Grid: Design Speculations for Manhattan.

Praise for the Greatest Grid

I visited the exhibition on January 13. While seeing it in person allowed me to appreciate the physical size of the maps, the exhibit’s most important component is theaccompanying book. Mirroring the layout of the exhibit, the book breaks down Manhattan’s physical history essentially into these components:

- Precedents: Law of the Indies, Philadelphia, etc.

- People: Commissioners, surveyors, and opponents

- Street Plan: Creation, protection, and construction

- Effects on Manhattan: Subdivision and property values

There are 13 chapters in total each with an overview essay. These essays are clearly written and reveal the authors’ deep understanding of the grid’s greater implications. For example, beginning chapter 4 on opening streets:

The miracle of the 1811 plan was that it was enforced. It took about sixty years for the grid to be built up to 155th Street, sixty years during which mayors and administrations, interest groups and aesthetic values frequently changed and might have undermined the plan–but the grid prevailed. New York sustained a multigenerational commitment to its first major infrastructure project–a rarity in the history of master plans, which are more often ignored or forgotten than implemented.

Following these introductions is a full series of photographs and maps with their own extensive captions. If you cannot see the exhibit in person, by all means purchase the book. The amount and quality of the material should make this required reading for everyone from developers to environmentalists.

Below are some of my photographs and thoughts from the exhibit.

Precedents for Manhattan’s grid include Christopher Wren’s plan for London in 1666 (top left); plan for Edinburgh in 1767 (bottom left); William Penn’s plan for Philadelphia in 1683 (top middle); James Oglethorpe’s plan for Savannah in 1732 (bottom middle); and the Land Ordinance of 1785 (right).

These large stone markers were placed by the surveyors as they marched methodically up and down the island. The physical size was necessary to thwart guerilla opponents of the grid who would otherwise uproot these markers thereby erasing the surveyors’ work.

At the center of the exhibit space rests John Randel’s large map of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The map measures 30 inches wide and 106 inches long!

At the center of the exhibit space rests John Randel’s large map of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The map measures 30 inches wide and 106 inches long!

This is my favorite photograph in the exhibit showing Lenox Farm at Madison Ave and 71st Street. Yes, a farm at Madison/71st! Central Park is in the background. It is amazing to see what is there now.

This is my favorite photograph in the exhibit showing Lenox Farm at Madison Ave and 71st Street. Yes, a farm at Madison/71st! Central Park is in the background. It is amazing to see what is there now.

Of course Le Corbusier had something to say about the grid.

Of course Le Corbusier had something to say about the grid.

Map detail. Just for reference, the MCNY is located on 5th Ave between 103rd and 104th.

Map detail. Just for reference, the MCNY is located on 5th Ave between 103rd and 104th.

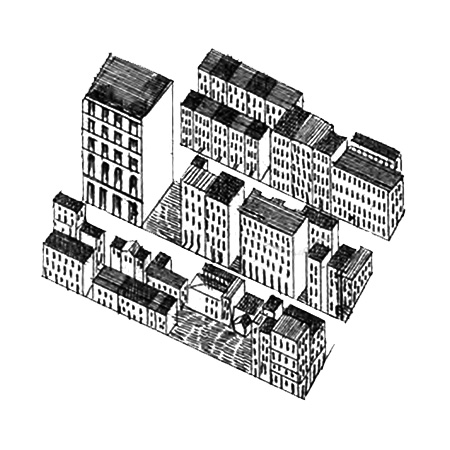

William Bridges’s print of John Randel’s surveying work.

William Bridges’s print of John Randel’s surveying work.

Overall, this is a deeply insightful exhibit on the grid plan. A visit will allow you to experience the greatest grid itself, but if you cannot make it certainly purchase the book.

Criticism

All that praise being said, unfortunately the MCNY’s other exhibit The Unfinished Grid: Design Speculations for Manhattan was lacking in both academic rigor and writing skill. The purpose of the exhibit was to have contributors

speculate about how Manhattan’s grid might be adapted, extended, or transformed in the future.

While some of the projects chosen for display were ok, most of them ignored the essential nuances and power of the street grid–its practical mathematics, efficiency in development, history, public access to private property, etc, etc. Most of them merely took the sophomoric approach of “breaking the grid” seemingly by a knee jerk reaction. The authors must have realized their projects lacked much substance because their statements were written as obscure architect-speak designed to conceal this fact. For example:

Allow me to attempt a translation:

Allow me to attempt a translation:

Architecture gives three-dimensional form to the two-dimensional grid. While the grid itself does not change, the architecture of Manhattan changes constantly over time. This causes one’s perception of the grid to change over time as well.

How hard was that? Again, this is a classic example of a designer overcompensating for a mediocre idea by flowering it up with unnecessary jargon.

In some cases the authors simply promoted their distantly related message whether it had anything to do with the grid or not. They did this graphically by shoving whatever cliché they chose into rectangles. For example, here is a project proposing an extension of the grid to harbor an ecological filtration system:

I am not saying that ecological filtration systems are a bad idea. I am only saying that in this project the grid was an obvious afterthought. This is counter to the Commissioners of 1811 who saw the inherent power of the grid itself–a preplanned, physical, and public framework upon which Manhattan could efficiently and incrementally grow. Does an ecological filtration system need the grid?

Finally, one designer triumphantly breaks the grid by proposing a highway interchange:

Hasn’t that already happened? Again, the author attempted to rescue this idea using architect-speak:

I hate to be so critical, but it was a shame to see such a well executed history and understanding of the Manhattan grid on the museum’s first floor only to be mostly ignored on the second. I would ask most of these contributors to revisit (or visit for the first time) the main exhibit.

The Greatest Grid:

http://www.mcny.org/exhibitions/current/The-Greatest-Grid.html

The Unfinished Grid:

http://www.mcny.org/exhibitions/current/The-Unfinished-Grid.html